Most heirs to long-dead sultanates would be laughed out of the room if they laid claim to modern territory on the basis of a 135-year old claim. Yet, with the self-styled Sultan of Sulu sending an armed gang to invade Sabah on the basis of such a claim, let us consider whether his claim is valid.

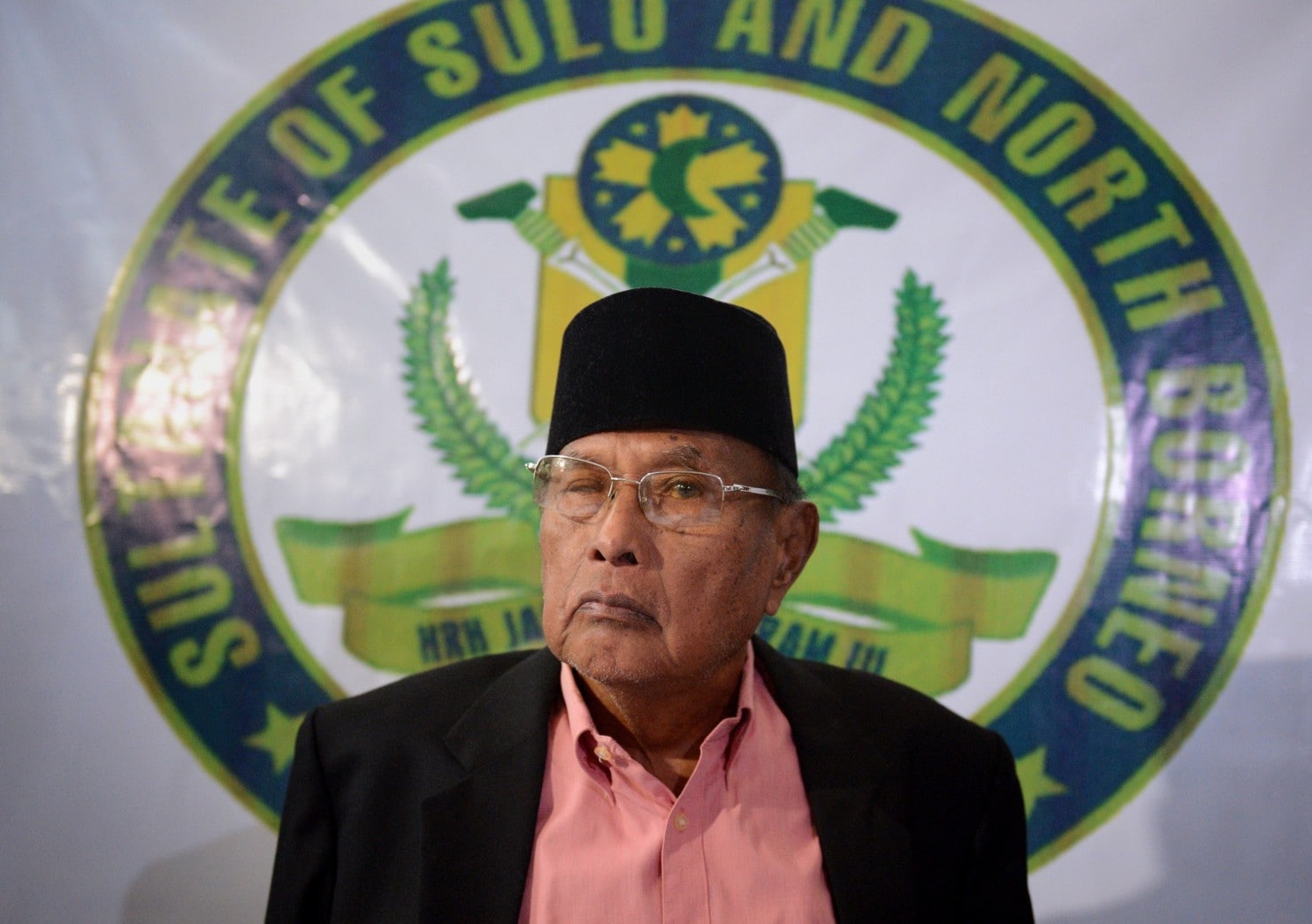

First of all, Jamalul Kiram is just one of nine claimants to the defunct title of Sultan of Sulu. He is by no means the recognised heir, rather he has chosen to call himself the “Sultan”, his brother the “Crown Prince”, and his daughter “Princess” etc. More importantly, the Sulu sultanate was itself abolished way back in 1917.

This would a laughable situation if the Kirams weren’t backed up by an armed gang, ready to kill in a desperate bid to be taken seriously.

The Sulu claim to Sabah stems from its acquisition by the Sulu sultanate in 1704 as a reward for helping the Sultan of Brunei to quell a rebellion. In 1878, the then Sulu ruler ceded the territory to the British North Borneo Company (NBC), which, in turn, transferred sovereign rights over Sabah to Britain in 1946.

When the British granted independence to the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, Sabah was one of the territories turned over to Malaysia, which continues to pay a token rent to the heirs of the Sulu sultanate to this day.

That in a nutshell is the history.

It is important to remember that, after Sabah was ceded to Britain in 1946, neither the Sulu clan, nor the Philippine government that was its formal successor, made any claim on Sabah till 1962. The fact that they didn’t see fit to raise this claim for sixteen years shows that they realised an opportunity much later.

In June 1962, the Philippine government lodged a formal claim to sovereignty over Sabah, or British North Borneo as they called it. But Malaysia’s claim proved far stronger.

The legal question centred on the translation of the Malay-Arabic word ‘pajak’ that appeared in the vernacular version of the 1878 agreement that handed Sabah over to the British North Borneo Company (NBC). In common parlance, the term could be used to denote both “to lease” or “to cede”.

The British and Malayan governments pointed out that the English language document agreed by the Sultan of Sulu categorically stated that the land was ceded “forever and until the end of time”, and not leased as the Philippines claimed.

Malaya’s position was further reinforced by the International Court of Justice ruling that “a historic title, no matter how persuasively claimed on the basis of legal instruments and exercise of authority, cannot – except in the most extraordinary circumstances – prevail in law over the rights of non-self-governing people to claim independence and establish their sovereignty through the exercise of bona fide self-determination.”

Indeed, in line with the internationally accepted principle of self-determination, the people of Sabah expressed their preference to join the larger Malaysian Federation through a free referendum in 1962 that was supervised by a United Nations fact-finding mission.

And again in the 1963 election, the majority of the people of Sabah showed they had no desire to be a part of the Philippines, or, for that matter, of the historical Sulu sultanate.

That is where the matter rests today. To mollify Jamalul Kiram, the Philippine government is now considering taking Malaysia to the International Court of Justice, but any Philippine claim to Sabah stands little chance of being recognised.

It is perhaps ironic that Sabah first came into Sulu possession in 1704 because they helped end an uprising, yet in 2013 the Sulu claimants are trying to regain it by attempting an armed intrusion themselves.

This is their last stab at history, before the Sulu claim will have to give way finally to the modern reality.